My piece for Weill Cornell Medicine Magazine

This was originally published in the Winter 2020 edition of Weill Cornell Medicine Magazine. See the full PDF of the publication here.

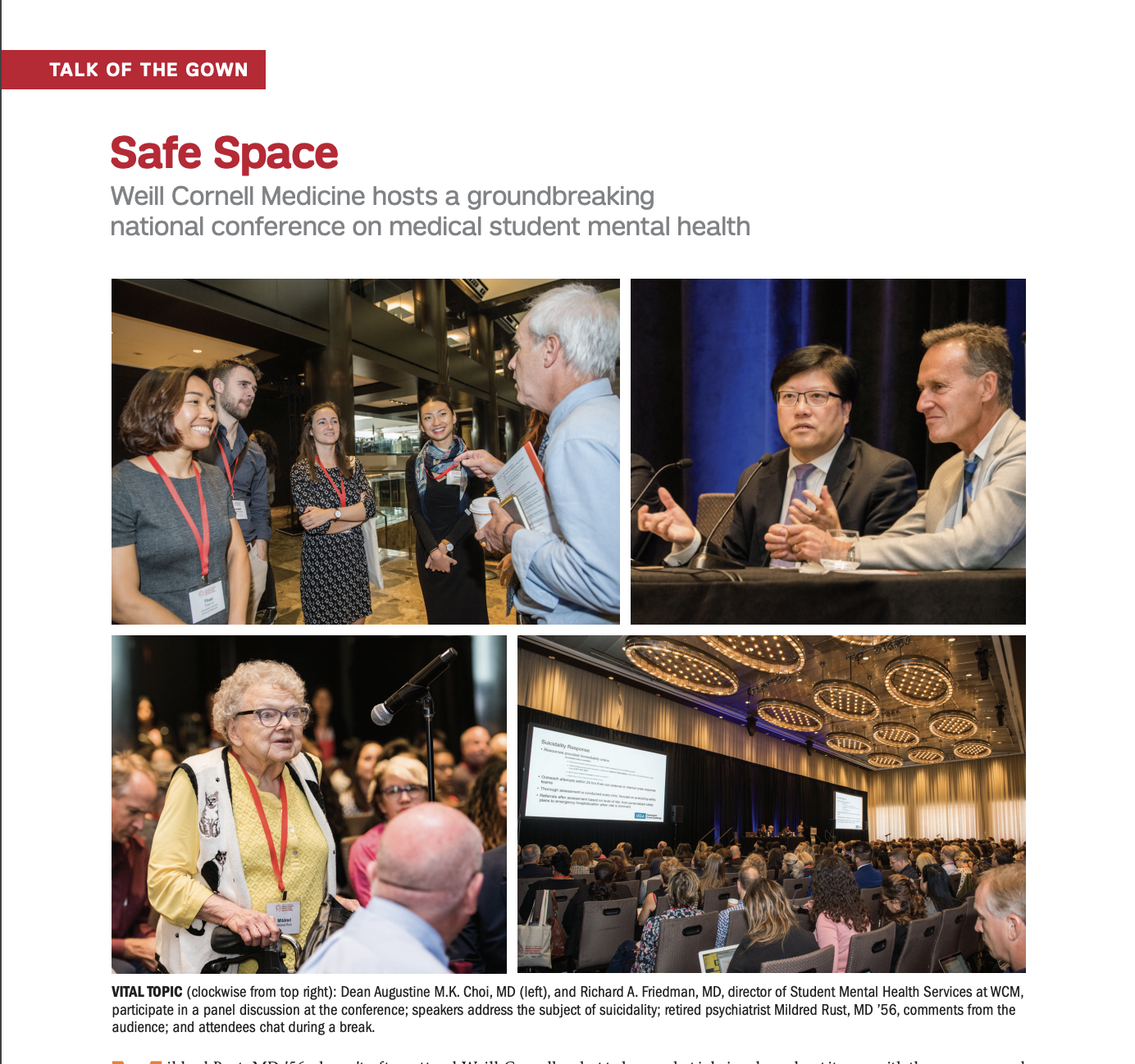

Safe Space

Weill Cornell Medicine hosts a groundbreaking national conference on medical student mental health

By Brian Mastroianni

Mildred Rust, MD ’56, doesn’t often attend Weill Cornell Medicine events. The ninety-one-year-old retired psychiatrist, who was one of only four women in her graduating class, currently lives far from Manhattan in a retirement community in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Living with Parkinson’s disease, it’s not always easy for her to travel—but she felt compelled to make the journey to attend the first-of-its-kind National Conference on Medical Student Mental Health and Well-Being.

“The topic is really important to me, because I have a history of depression,” Rust explains. “I was depressed in medical school. I had good treatment, but to know what is being done about it now, with the programs and so forth, is very important. Weill Cornell’s openness and respect, as shown to me by my classmates and faculty when I was a student, foresaw its attitudes in its current programs and in initiating this conference. That was another reason why I had to come.”

Rust was one of more than 350 medical school educators, mental health professionals, students, and researchers who attended the two-day symposium in September, hosted by Weill Cornell Medicine in partnership with the Association of American Medical Colleges, Associated Medical Schools of New York, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Designed to address the increasing rates of psychological distress among medical students nationwide, the event spotlighted the findings of leading mental health researchers, clinicians, and educators while giving a needed platform for students and stakeholders to de-stigmatize the conversation around mental health.

The symposium served as a safe space for frank discussions about what the medical school climate has been like in the past, where it is now, and what needs to change for the future. In 2014, researchers from the Mayo Clinic and Stanford University published a paper in Academic Medicine, the journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, that found more than half of medical students in the U.S. experienced symptoms of depression. In the same report, students were found to be up to five times more likely to live with clinical depression than college-educated peers in other fields.

In an opinion piece published on the medical news site STAT a month ahead of the conference, Augustine M.K. Choi, MD, the Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Dean of Weill Cornell Medicine, cited that paper and wrote that “for many generations of students, medical school has traditionally promoted a culture of self-sacrifice over self-care,” adding that the “pressure to perform academically is relentless.”

Choi’s piece sounded the alarm for institutional change, stressing the fact that students training to safeguard the health and well-being of others must also care for themselves.

During the conference’s opening session, Choi stood before the audience in the hotel ballroom of the Grand Hyatt New York with a similar call to action.

“Arguably, medicine is the most noble profession,” he said, “and we have to intervene so we’re not placing so much stress on our students and preventing them from becoming the best doctors they can be.”

His remarks launched two days of presentations from a range of researchers and mental health advocates. They highlighted such topics as reassessing how medical schools handle the stresses of exams and the challenges faced by student populations often underrepresented in medicine.

While most of the attendees were clinicians, researchers, and administrators from other medical schools, about twenty WCM students—including those pursuing MDs, PhDs, and physician assistant degrees—were in the audience.

MD-PhD candidate Andrew Griswold, who serves as the student representative to WCM’s Board of Overseers, called the conference “incredibly useful,” adding that one of the highlights for him and his fellow students was connecting with people from other schools around the country.

“It was a great opportunity to hear about what struggles other institutions face and what best practices have emerged,” he says. “My main takeaway from the two days of presentations is that there is a community of faculty, staff, and—most importantly—students who care deeply about improving student mental well-being and will be a resource for tackling this national crisis.”

He says he was encouraged to see WCM not only address the issue head-on, but use the symposium as a way to elevate the topic on the national stage.

“It’s quite powerful that over 350 people attended the first conference,” he says, “and that attendees expressed interest in making this a regular event.”

Lisa Meeks, PhD, an assistant professor of family medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School who spoke at the conference, says she “was touched by the self-disclosure of many of the presenters and audience members.”

Her own lecture on students with psychological disabilities such as depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder looked critically at medical schools’ standard responses to student mental health concerns. Oftentimes, this means that schools utilize leave of absence policies that are one-size-fits-all in their scope, failing to take into account the vast spectrum of experience that comes with different psychological disabilities.

Of the conference itself—which also included yoga breaks and networking sessions—Meeks says bringing so many different people together to tackle how the medical school culture can change is a “major shift.”

On the second day, the entire ballroom was especially moved by the conversations around suicide. In her talk, Christine Moutier, MD, chief medical officer for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, stressed that suicide is one of the most under-treated and mismanaged health conditions and that officials in academic medicine have to “become the helpers who are walking the walk of what science is telling us.”

Later in the session, Timothy Marchell, PhD, director of the Skorton Center for Health Initiatives at Cornell Health (the health center on the Ithaca campus), reflected on the life’s work of his friend and colleague Greg Eells, PhD, the center’s former head of counseling and psychological services; Eells, who had moved to a similar job at another university, had taken his own life the previous week.

It underscored one of the larger themes Choi touched on in his own remarks: sometimes caregivers need care themselves.

It’s a dynamic Rust knows all too well.

Despite having specialized in psychiatry, it has only been in recent years—encouraged by an article from the National Alliance on Mental Illness on the healing power of storytelling—that she has been publicly open about her own history of mental health struggles as a medical student.

“Very few people where I lived knew about it, but it turned out to be very good for me,” Rust says. “It felt good to be open.”

See the full issue here.